Planning and Operations

Do Nothing – the Hardest Option

A recent exercise was set in an imaginary developed country. The aim was to ensure that the Task Force being trained could concentrate on its warfighting function and for once, not have to worry unduly about all the other issues which make demands on a Commander’s time and resources. No problem with this – if a Force cannot fight a battle when required then there is little point in having it.

However, the Task Force response was surprising. Even when they were told that they did not need to do something they still tried to do it. The Host Nation stated quite clearly that they did not want their police being trained by the force but a dutiful planner was nevertheless given the task. No need to worry about refugees, the police and emergency services had it covered. Similarly, Special Branch could deal with the CT threat. A sceptical Task Force decided not to take the risk and assembled the assets necessary to provide the Host with something it didn’t need or want.

Prudence or arrogance? Whichever it may have been, the staff were very uncomfortable being put into this position. There was a vague sense that they were not fulfilling their task. But what should one do under these circumstances? If you do not believe the Host Nation then by any standard contingency planning seems sensible. But what to do if despite your best efforts they still don’t need or want any help? Surely this is what we are after?

There is an old military saying of ‘lead, follow or get out the way – but do something’. Perhaps getting out the way is sometimes overlooked when perhaps it should be more readily considered. After all, you trust your ally don’t you?

Unless there is a truly Integrated Approach amongst all stakeholders then intervention operations in failed or failing states are unlikely to succeed. The problems facing the host nation are normally challenging enough without a fragmented and unco-ordinated international response. And yet, while it sounds so obvious we are often our own worst enemies. The ability to work collectively requires time, effort and management.

This should not be seen as a purely civ-mil challenge - the 'civ-civ' or 'mil-mil' dimensions can also be a source of friction. Whether the sectors are Government, NGO, Private Sector or Military clear lines of accountability are essential. Everyone must know what is expected of them and then be given the space to deliver it.

Those who dare

Whenever I hear of yet another food convoy making its way into some isolated and troubled refugee camp my first thoughts are not with the fortunate recipients. I am not being deliberately callous but they are there because a set of appalling circumstances led them there and generally speaking they had no choice. At least the resupply offers some respite.

It's the drivers I think of. They have a choice. OK they are largely paid contractors but no-one says they have to do it. Unarmed, utterly reliant on the badge on their trucks and the tenuous goodwill of besieging militias or armies - no big military umbrella for them. There is a world of difference between doing these tasks in uniform or civvies.

Group Think and the Red Team

A recent BBC World Service programme recently covered the issue of group think. Try iPlayer and you might still catch it but it’s worth a listen. Highlighting the challenge of everyone going along with a plan even when they know it is likely to fail, the concept of Red Teaming soon came up. The interviewee ruefully acknowledged that despite his best efforts everyone found the process awkward. He is not alone. I well remember the one star who, on being confronted with a challenging issue, dismissed it with the words ‘We don’t want to disrupt the plan’. At least he was upfront about it – in most cases Red Team ideas (or perhaps more accurately, junior management concerns) are acknowledged and then quietly ignored.

It’s difficult to strike a balance between action and analysis. Risk and it’s mitigation absorb a lot of managerial time. Rightly so but there comes a time when you have to jump. The military planning process allows for dissenting voices but its application can be so status driven that it takes a very brave man or woman to put their head above the metaphorical parapet before doing the same thing to a real one.

I suggest that systems should be more robust. The staff should be assembled and asked directly ‘What is wrong with this plan?’ It should be led by the CoS and concerns should not be defended to the death by an aggrieved SO1. The Commander should be presented with an agenda which is a considered summary of possible land mines. The staff in return must be sufficiently disciplined to use the time responsibly and not just as a whingers charter.

Why wouldn’t you want this in any organisation? If your team do not believe in what they are doing wouldn’t you want to know why? I’m pretty sure some readers will assert that the current Crisis Planning Team process allows for the concerned planner to have their say. I would agree up to a point but have you seen it working well recently? Really? What does the group think?

The Context

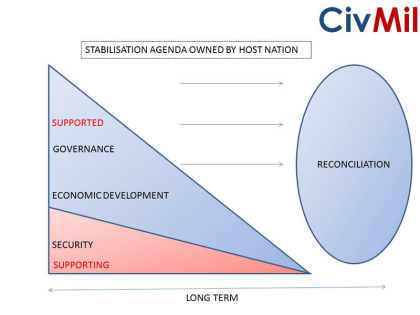

In defining lines of accountability for civmil actors there needs to be a clear understanding of the operating environment. I use the following diagram to illustrate the key principles for a unified programme:

The most crucial point is that the agenda belongs to the host nation. The International Community can apply its influence but ulitmately it is there to support a nation that must find its own way. Reconciliation may take many forms but ultimately unless it happens at a local level it cannot be imposed.

It is governance and development which will deliver stability. This is the core. The challenge for the civilian community is to develop coherent and credible strategies which support these critical lines of operation.

The military meanwhile are there to provide a secure environment in which the civilians can function. In a nutshell this is about freedom of movement. The challenge for military commanders is to stay in lane and not get distracted by finding other tasks. And again, it is the Host Nation security forces which will set the agenda and they must be given the space to do so.

Finally how long is the 'long term'? As short as possible but as long as it takes. Otherwise dont go.